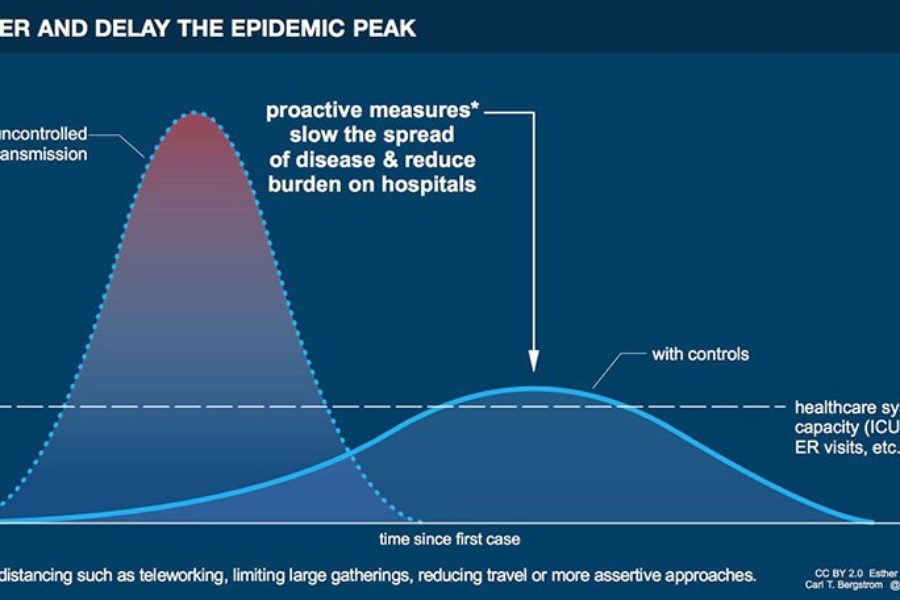

Welcome back to my #FlattenTheCurve series. If you are new please be sure to check out my first post about flattening the curve of COVID-19, my follow up where I discussed Vitamin C or D, my third post centering on zinc and the spice turmeric, and my fourth post concerning elderberry, garlic, and Echinacea. Today I we will take a look at the supplements NAC and quercetin. As I have mentioned throughout this series, as of today, there is no proven cure or preventative treatment for COVID-19. All we can do is try to do our best to aid our immune system through diet, supplements, sleep, stress management techniques, and moderate intensity physical activity.

NAC (N-acetyl cysteine)

NAC is a modified form of the amino acid cysteine. While cysteine is naturally found in foods, NAC is not. Instead, our bodies naturally produce this chemical because NAC then goes on to be transformed into the body’s chief biochemical antioxidant glutathione. Without glutathione, many of our body’s essential metabolic reactions wouldn’t be able to occur without causing major damage to the cells where the reactions take place. Like many of the nutrients I have evaluated in this series, NAC’s evidence is mixed. A 1997 study found that 600mg of NAC taken twice daily did reduce symptoms of the flu but it did not prevent a person from catching it.1 The participants took the supplement during the flu season. Meanwhile, a 2000 study found that natural killer cells (a type of immune cell) was restored in people with HIV.2 I urge caution though because of the lack of follow up studies as well as knowing that there is more to our immune system than increasing the activity of one type of immune cell. Some other studies centered around chronic bronchitis and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) reveal that 400-600mg of NAC taken daily could potentially reduce the worsening of chronic bronchitis or COPD.3,4 Since there is no way to get NAC from foods, if you decide you want to start taking NAC, you will have to resort to a supplement.

Quercetin

We see this chemical all the time and most don’t realize it. Quercetin is a flavonoid antioxidant that gives yellow foods its color but is also found in foods such as onions or kale. Like many nutrients, we have a variety of animal studies showing potential benefits from using quercetin, but like many nutrients, we have few double blind randomized controlled trials in humans.5,6 Those that we do have tend to be small such as a 2007 study of 40 male cyclists taking 1000mg of quercetin before, and then after intense exercise.7 The study showed less upper respiratory infections in the quercetin versus the placebo group but, again, this is a very small study and was performed on athletes and not the general poulation.7 That being said, studies do show that quercetin can inhibit the growth of some viruses including the flu, but also SARS-CoV.8

Since quercetin has better absorption from foods than supplements, and considering all the other beneficial chemicals in vegetables and fruits, I would focus on trying to increase you intake by focusing on foods first. If you primarily eat the standard American diet (SAD) of processed, refined, or fast foods you will most likely get a greater benefit from focusing on increasing whole fruits and vegetables versus relying on supplements. Some may argue that it’s hard to get the doses found in supplements from food. That is certainly true, but food has synergistic activity that you will never get from a supplement. If new data comes out showing quercetin has benefits in for the treatment of COVID-19 I will let you know.

While quercetin is generally well tolerated in most people, and especially if taken with food (since most side effects are mild and gastrointestinal in origin), it may have an impact on the thyroid based on lab and animal studies.9, 10, 11 It’s important to note though that no studies have been performed in humans to see if quercetin impacts thyroid health. If you have hypothyroidism, or are pregnant or nursing, then it’s probably best to avoid quercetin until more research has been performed.

References:

1. De Flora, S., Grassi, C., & Carati, L. (1997). Attenuation of influenza-like symptomatology and improvement of cell-mediated immunity with long-term N-acetylcysteine treatment. European Respiratory Journal, 10(7), 1535–1541. doi:10.1183/09031936.97.10071535

2. Dröge, W., & Breitkreutz, R. (2000). Glutathione and immune function. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 59(04), 595–600. doi:10.1017/s0029665100000847

3. Grandjean, E. M., Berthet, P., Ruffmann, R., & Leuenberger, P. (2000). Efficacy of oral long-term N-acetylcysteine in chronic bronchopulmonary disease: A meta-analysis of published double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials. Clinical Therapeutics, 22(2), 209–221. doi:10.1016/s0149-2918(00)88479-9

4. Pela, R., et al. (1999). N-Acetylcysteine Reduces the Exacerbation Rate in Patients with Moderate to Severe COPD. Respiration, 66(6), 495–500. doi:10.1159/000029447

5. Li, Y., et al. (2016). Quercetin, Inflammation and Immunity. Nutrients, 8(3), 167. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8030167

6. Somerville, V. S., Braakhuis, A. J., & Hopkins, W. G. (2016). Effect of Flavonoids on Upper Respiratory Tract Infections and Immune Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md.), 7(3), 488–497. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.115.010538

7. Nieman, D.C., et al. (2007). Quercetin Reduces Illness but Not Immune Perturbations after Intensive Exercise. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 39(9), 1561–1569. doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e318076b566

8. Chen, L., et al. (2006). Binding interaction of quercetin-3-β-galactoside and its synthetic derivatives with SARS-CoV 3CLpro: Structure–activity relationship studies reveal salient pharmacophore features. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 14(24), 8295–8306. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.014

9. Andres, S., et al. (2017). Safety Aspects of the Use of Quercetin as a Dietary Supplement. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 62(1), 1700447. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201700447

10. Giuliani, C., et al. (2014). The flavonoid quercetin inhibits thyroid-restricted genes expression and thyroid function. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 66, 23–29. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2014.01.016

11. De Souza dos Santos, M. C., et al. (2011). Impact of flavonoids on thyroid function. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 49(10), 2495–2502. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2011.06.074