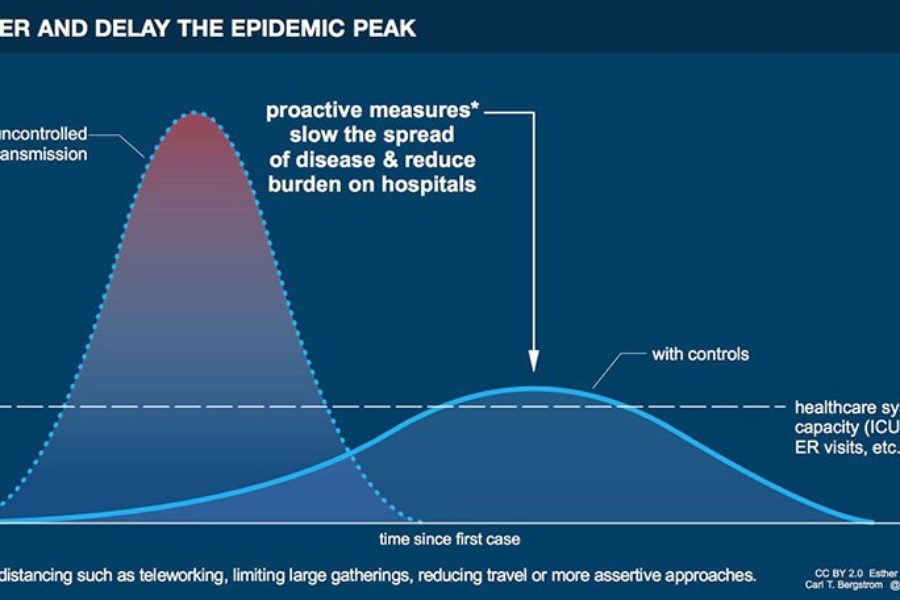

In my first post concerning #FlattenTheCurve, I discussed the importance of flattening the curve and some basics people can do to help slow the spread of this pandemic. My second post discussed the pros and cons of taking either Vitamin C or D for the immune system. Today I will be discussing zinc, and the herb turmeric. In my previous posts I discussed considerations such as synergy of nutrients from whole foods and so I encourage you to read those posts to learn more about this concept as I will do my best to be concise and not repeat what I have written in other parts of this series.

For a time, Vitamin C was the fad nutrient being pushed by supplement manufacturers and their sales people. At some point zinc managed to find it’s way near the top of the pack of nutrients most commonly suggested for prevention of infections from viruses.

Zinc (and Selenium)

Like Vitamin C and D, zinc’s usefulness may have more to do with how deficient the average American is than any specific “healing” attribute related to zinc itself. Zinc is involved with hundreds of metabolic reactions in the body and thus it is no stretch to imagine that being deficient in this mineral also means that our ability to perform these reactions efficiently will be hampered…leading to decreased immune functioning. That being said, we do know that the elderly tend to have lower levels of nutrient absorption across the board and so the elderly are the most likely to benefit from supplementation. This is great news considering the elderly have the greatest risk of catching COVID-19. A study of elderly people in nursing facilities in France showed that supplementing with 20mg per day of zinc (with 100mcg of selenium) could potentially lower the chance of catching a respiratory tract infection.1 In addition, the study also showed that supplementation with zinc (and selenium) could result in an improved antibody response to the flu vaccine.1 One caveat about this study though is that most of the participants were deficient at the time the study was performed (zinc and selenium), so we don’t know how much the benefit was from zinc supplementation verses just getting a person’s zinc in the body to where it needs to be for normal functioning.1 The AREDS study, provides some other data. This study showed us that 60mg of daily supplementation of zinc for five years was protective against death from respiratory infections when compared to no zinc in a study group with a median age of 69.2

Both these studies show a potential benefit of zinc supplementation for the elderly, so if you are in a high risk age group, or suffer from gastrointestinal issues, supplementation with 20mg of zinc could prove beneficial. How about everyone else?

There is some evidence that zinc supplementation could be beneficial for other groups as well. Once again though, the benefits seem to come from correcting a zinc deficiency. This study by Yıldırımyan et al., showed that correcting a zinc deficiency (as well as an iron deficiency when present) in people with canker sores was able to stop recurrence of the sores.3 When it comes to colds, there is some more evidence suggesting a benefit from zinc. One major piece of evidence includes a review of three randomized placebo-controlled trials showing that 80-92mg of zinc in lozenge form (more in a little bit about why lozenges seem to be more beneficial when using zinc for respiratory tract infections) taken at multiple intervals throughout the day at 9-13.3mg of zinc per dose was able to reduce cold syptoms.4 It must be noted though that these results only apply to supplementation within 24 hours of onset of cold symptoms. Interestingly, a study out of Finland (with an average age of 49) showed us that lozenges from zinc dissolved in the mouth five to six times daily did not shorten the duration of colds.5 The authors speculate that this result may be due to many of the participants taking only five rather than six lozenges a day. This put the average supplemental intake at 65mg per day. This is lower than the study mentioned above. On top of this, the lozenges were smaller and dissolved more rapidly than lozenges used in the previously mentioned study.5 This study confirmed speculation as to why slow dissolving lozenges may be more beneficial than a fast dissolving lozenge or a pill. The theory is that zinc needs sufficient time to be absorbed by the cells in the throat and mouth for it to be effective, providing evidence that there may be a bit more to zinc than correcting a deficiency.

Like most of the minerals, there is an upper limit to zinc and there are potential side effects to consider while supplementing. The major issue with zinc supplementation is due to zinc’s interaction with other minerals, principally copper.6 These two minerals compete and so intakes above the RDA for extended periods of time (1-2 weeks) are not advised due to the risk of developing a copper deficiency which will cause a host of its own problems. To try and avoid this, many higher end zinc supplements now have 1-3mg of copper in them as well. In case you were ever wondering why this was in the formulation, well, now you know. In addition to copper, zinc (and high doses of calcium, magnesium, and the ferrous form of iron) has been shown interfere with the absorption of the carotenoids beta-carotene, lycopene, and astaxanthin from food as well as supplements. These are important chemicals for our health and so if high doses of zinc are being used then it’s best to take zinc several hours before or after consumption of carotenoids (think foods with orange-yellow pigment in them such as sweet potatoes, carrots, butternut squash, cantaloupe, red bell peppers; but also spinach, lettuce, and broccoli.

Turmeric/curcumin

Turmeric is having its moment in the spotlight and I must admit there is a lot of research on a variety of different uses for turmeric/curcumin for medical issues. First let’s clarify why I wrote turmeric as well as the word curcumin. Turmeric is a spice used throughout the Middle East and Asia but the active ingredients are chemicals called curcuminoids, curcumin being the most well studied and most beneficial.

As mentioned above, the anti-inflammatory effects of turmeric are well known for a wide variety of conditions. That being said, it’s important to consider how useful turmeric may be when it comes to inhibiting viral activity if we want to be clear about the potential benefit of using turmeric for immune health. There is some research to suggest that curcumin may be helpful for viruses such as the flu, hepatitis C, and Zika because it has some antiviral effects.7,8 Some animal studies have shown that curcumin may have protective qualities for the lungs when curcumin is injected.9,10,11 I don’t like to rely on animal studies because many animal studies will show a benefit for an intervention that doesn’t pan out in human trials. In addition, while all mammals share many metabolic processes there are still enough differences that I prefer to rely on human studies. Luckily there is a small human study we can refer to. This study is a very small 2009 study out of Italy showing 100mg of curcumin (with 900mg of lactoferrin) taken three times per day could reduce recurrent respiratory infections when taken for four weeks.12

As word spread across the globe of the emerging threat of COVID-19 scientists have stepped up to find novel ways to treat this virus. In addition, other scientists are trying all sorts of nutrients and herbs to try and aid in the fight against the virus. Time will tell which ones work and which are hype. As of now all we have to go off are small studies that have not completely passed through the peer review process. Due to the seriousness of the disease doctors in urgent care and intensive care units at hospitals will be making tough decisions and trying therapies that have not fully been shown to be helpful. These physicians are well trained and use lab work to minimize side effects and potential toxicity of some of the substances being considered. This means that as far as we are concerned it’s still important to stick to trials that have been peer reviewed in order for the general public to avoid toxicity caused by dose or type. Due to the limited human studies using curcumin, my recommendation is that curcumin may have lots of potential to aid our body with the inflammatory process in general but we don’t have enough data to tell if it’s significant enough to warrant its use over other supplements for protection against COVID-19.

The safety of curcumin may depend on predisposition to certain diseases or use of certain medications but otherwise its use is well established and dosages as high as 8 grams (8,000mg) per day are considered safe for most people with only mild side effects.13,14,15 Some of these side effects include headache, nausea, diarrhea, yellow stool, and allergic skin reactions.13,14,15 This being said there are still considerations to take account, such as a 2002 study showing that turmeric can stimulate gallbladder contractions which could lead to pain in those passing gallstones or those with gallbladder disease.16 A variety of case studies show us that in a very small subset of the population (mostly women), turmeric used for longer than a month could have a negative impact on liver function.17,18,19,20,21 In those who have a predisposition to kidney stones, turmeric supplements may trigger kidney stone formation. This is due to the oxalate in some, but not all, turmeric supplements, which binds to calcium, forming calcium oxalate kidney stones.22 The oxalate can be significant for those on medically necessary low oxalate diets. In addition to its anti-inflammatory properties, turmeric has blood thinning properties as well.23 Turmeric’s blood sugar lowering effects could also make it’s use risky for those taking diabetes medications.24 A few studies have shown that curcumin may reduce the bioavailability of iron by binding to it.25, 26, 27 This can eventually lead to anemia or worsen it. If you have anemia, its best to take curcumin at least 3 hours after eating a meal rich in iron or when taking an iron supplement and do so under the supervision of your health care provider. If you have any of the conditions or are on any of the medications mentioned above, talk with your health care provider before use of turmeric.

In the next chapter of this #FlattenTheCurve series I will discuss elderberry, garlic, and echinacea. Until then, be well everyone.

References

1. Girodon, F. (1999). Impact of Trace Elements and Vitamin Supplementation on Immunity and Infections in Institutionalized Elderly Patients. Archives of Internal Medicine, 159(7), 748. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.7.748

2. Associations of Mortality With Ocular Disorders and an Intervention of High-Dose Antioxidants and Zinc in the Age-Related Eye Disease Study. (2004). Archives of Ophthalmology, 122(5), 716. doi:10.1001/archopht.122.5.716

3. Yıldırımyan, N., et al. (2019). Recurrent Aphthous Stomatitis as a Result of Zinc Deficiency. Oral Health Prev Dent, ;17(5):465-468. doi:10.3290/j.ohpd.a42736.

4. Hemilä, H., & Chalker, E. (2015). The effectiveness of high dose zinc acetate lozenges on various common cold symptoms: a meta-analysis. BMC Family Practice, 16(1). doi:10.1186/s12875-015-0237-6

5. Harri, H. et al. (2020). Zinc acetate lozenges for the treatment of the common cold: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 10:e031662. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031662

6. Poujois, A., Djebrani-Oussedik, N., Ory-Magne, F., & Woimant, F. (2018). Neurological presentations revealing acquired copper deficiency: diagnosis features, aetiologies and evolution in seven patients. Internal Medicine Journal, 48(5), 535–540. doi:10.1111/imj.13650

7. Mounce, B. C., et al. (2017). Curcumin inhibits Zika and chikungunya virus infection by inhibiting cell binding. Antiviral Research, 142, 148–157. doi:10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.03.014

8. Mathew, D., & Hsu, W.-L. (2018). Antiviral potential of curcumin. Journal of Functional Foods, 40, 692–699. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2017.12.017

9. Almatroodi, S. A., et al. (2020). Curcumin, an Active Constituent of Turmeric Spice: Implication in the Prevention of Lung Injury Induced by Benzo(a) Pyrene (BaP) in Rats. Molecules, 25(3), 724. doi:10.3390/molecules25030724

10. Punithavathi, D., Venkatesan, N., & Babu, M. (2000). Curcumin inhibition of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in rats. British Journal of Pharmacology, 131(2), 169–172. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0703578

11. Avasarala, S., et al. (2013). Curcumin Modulates the Inflammatory Response and Inhibits Subsequent Fibrosis in a Mouse Model of Viral-induced Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. PLoS ONE, 8(2), e57285. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0057285

12. Zuccotti, G., et al. (2009). Immune modulation by lactoferrin and curcumin in children with recurrent respiratory infections. Journal of biological regulators and homeostatic agents. 23. 119-23.

13. Burgos-Morón, E., et al. (2010). The dark side of curcumin. International Journal of Cancer, NA–NA. doi:10.1002/ijc.24967

14. Lao, C. D., et al. (2006). Dose escalation of a curcuminoid formulation. BMC complementary and alternative medicine, 6, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-6-10

15. Dhillon, N., et al. (2008). Phase II Trial of Curcumin in Patients with Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 14(14), 4491–4499. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-08-0024

16. Rasyid, A., Rahman, A. R. A., Jaalam, K., & Lelo, A. (2002). Effect of different curcumin dosages on human gall bladder. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 11(4), 314–318. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.2002.00296.x

17. Lee, B.S., et al. (March, 2020). Autoimmune hepatitis association with turmeric consumption. ACG Case Reports Journal, 7(3):e00320. doi:10.14309/crj.0000000000000320

18. Luber, R. P., et al. (2019). Turmeric Induced Liver Injury: A Report of Two Cases. Case Reports in Hepatology, 2019, 1–4. doi:10.1155/2019/6741213

19. Abdullah, M.A., et al. (2019). Turmeric-associated liver injury. American Journal of Therapeutics 0, 1–4. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001025

20. Suhail, F. K., et al. (2019). Turmeric supplement induced hepatotoxicity: a rare complication of a poorly regulated substance. Clinical Toxicology, 1–1. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1632882

21. Imam, Z., et al. (2019). Drug Induced Liver Injury Attributed to a Curcumin Supplement. Case Reports in Gastrointestinal Medicine, 2019, 1–4. doi:10.1155/2019/6029403

22. American Urological Association. (2019). Medical management of kidney stones. Retrieved from: https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/kidney-stones-medical-mangement-guideline#x2870

23. Shah, B. H., et al. (1999). Inhibitory effect of curcumin, a food spice from turmeric, on platelet-activating factor- and arachidonic acid-mediated platelet aggregation through inhibition of thromboxane formation and Ca2+ signaling. Biochemical Pharmacology, 58(7), 1167–1172. doi:10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00206-3

24. Neerati, P., Devde, R., & Gangi, A. K. (2014). Evaluation of the Effect of Curcumin Capsules on Glyburide Therapy in Patients with Type-2 Diabetes Mellitus. Phytotherapy Research, 28(12), 1796–1800. doi:10.1002/ptr.5201

25. Tuntipopipat, S., Zeder, C., Siriprapa, P., & Charoenkiatkul, S. (2009). Inhibitory effects of spices and herbs on iron availability. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 60(sup1), 43–55. doi:10.1080/09637480802084844

26. Jiao, Y., et al. (2008). Curcumin, a cancer chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic agent, is a biologically active iron chelator. Blood, 113(2), 462–469. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-05-155952

27. Smith, T. J., & Ashar, B. H. (2019). Iron Deficiency Anemia Due to High-dose Turmeric. Cureus, 11(1), e3858. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.3858